A Preliminary Macroeconomic Analysis of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”

Key Points

- The House version of the “One Big, Beautiful Bill” Act (OBBBA) would extend major portions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), enact a handful of Trump’s campaign proposals, and enact several offsets that target low-income households, immigrants, and corporations.

- It would impact incentives to work, save, and invest. However, the effects would be mixed and vary over the next decade and over the long run.

- It would boost long-run economic output by 0.3 percent by increasing labor supply. However, it would reduce investment, especially in homeowner-occupied housing and C corporate assets, and have a negative impact on worker productivity and wages.

- Over the next decade (2026 to 2035), the OBBBA would increase economic output by 0.6, on average, but the impact would decline over time due to expiring tax provisions and the impact of federal borrowing on private investment.

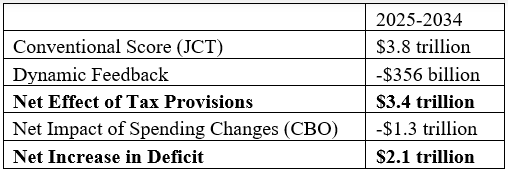

- The higher output over the budget window would result in modest dynamic revenue feedback of $356 billion over a decade, reducing the bill’s deficit impact from $2.4 trillion to $2.1 trillion.

- This paper analyzes the House-passed version of the OBBBA. This analysis will be updated as lawmakers make changes to the legislation.

Introduction

On May 22nd, the House of Representatives passed their version of the “One Big, Beautiful Bill” Act (OBBBA). The OBBBA extends and enhances the expiring provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), introduces a handful of President Trump’s campaign tax proposals, and offsets some of the cost of these tax cuts with tax increases and spending reductions that target low-income households, immigrants, and inbound foreign investment.

Tax policies generally impact the economy in three ways. In the short run, changes in taxes can impact the after-tax resources available to households, which can increase the demand for goods and services in the short run. In the long run, taxes influence economic output by influencing the supply of labor and capital. Finally, changes in federal borrowing due to tax changes can also impact the broader economy by impacting either investment or foreign claims on future US output.

The OBBBA, by changing the after-tax returns to work, saving, and investment, will have an impact on the US economy in both the short run and the long run. These macroeconomic effects are important to consider because they have direct effects on households and the federal government’s finances.

The main analysis in this paper focuses on the long-run impact of taxes on the supply of labor and capital and how that impacts long-run economic output. As such, it considers how changes to the marginal tax rate on labor impacts the after-tax wage and labor supply and how taxes on capital impact the cost of capital and the long-run size of the capital stock. Importantly, this analysis assumes that changes in government borrowing are entirely offset with non-distortive tax increases or spending reductions. This is perhaps unrealistic, but it isolates the impact of the tax changes on the economy.

This paper also produces a budget window estimate of the average increase in output over the ten years following the passage of the OBBBA. In contrast with the long-run estimate, this estimate incorporates the impact of additional borrowing over the budget window and its impact on interest rates, the capital stock, and economic output. This estimate is combined with a revenue estimate from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and spending projections by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to produce a dynamic budget score.

Major Components of the OBBBA

The core of the OBBBA is permanent extension of most of the major individual income tax provisions of the TCJA. This includes the lower statutory tax rates, the reformed family benefits, higher alternative minimum tax and estate and gift taxes exemption thresholds, limitations on the state and local tax deduction and the home mortgage interest deduction, and Section 199A, the deduction for qualified business income.

The OBBBA makes a handful of changes to the individual provisions of the TCJA. It temporarily enhances the standard deduction and the child tax credit. It permanently increases the estate and gift tax exemption threshold marginally. It increases the Section 199A deduction from 20 percent to 23 percent and reforms how its limitations phase in. It increases the state and local tax deduction limitation from $10,000 to $40,000 with a phaseout for high-income households.

It also replaces the Pease limitation on itemized deductions with a new limitation on itemized deductions that caps the tax value of deductions for tax filers with taxable income in excess of the top statutory tax rates at 35 percent. The limitation is 32 percent for the state and local tax deduction.

The OBBBA also includes three of President Trump’s individual income tax cut campaign promises. The Act introduced a new per person $4,000 deduction for seniors and exempts tips and overtime for qualifying workers. Finally, up to $10,000 in interest paid on qualifying auto loans is deductible against a taxpayer’s adjusted gross income.

The OBBBA temporarily extends 100 percent bonus depreciation and temporarily reverses amortization of R&D and a looser limitation on net interest deductions. It also introduces temporary expensing for certain qualifying manufacturing structures.

The bill extends and modifies the three major international tax provisions introduced by the TCJA: global intangible low-tax income, the foreign derived intangible income (FDII), and the base erosion anti-abuse tax (BEAT). The tax rates on all three of these provisions would rise modestly from their current policy levels. In addition, the bill introduces a new set of retaliatory taxes on inbound investment.

In addition to these major provisions, the bill introduces dozens of smaller provisions, such as expansions to “Achieving a Better Life Experience” (ABLE) accounts and HSAs, and introduces what are called “Trump Accounts” for households with children. The OBBBA repeals most of the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits for green energy investments and consumer goods. It also tightens eligibility for several tax credits for low-income households.

Impact of OBBBA on Work Incentives

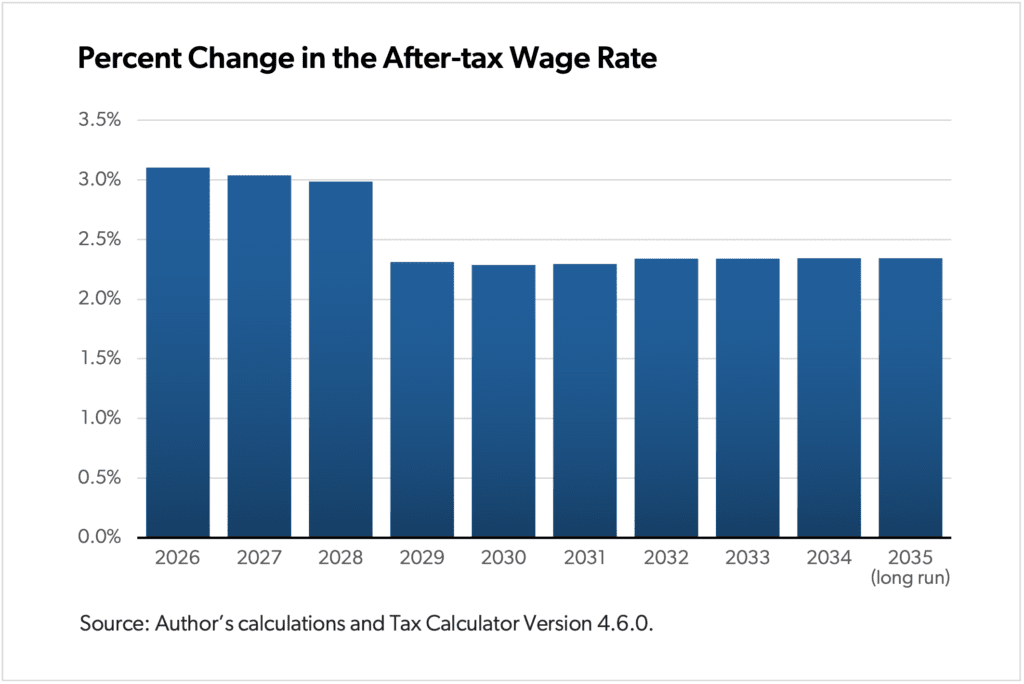

On net, the OBBB would improve work incentives. It would increase after-tax wages by reducing the marginal tax rate on labor earnings. However, the effect would vary over the next decade. The figure below shows the percent change in the economy-wide after-tax wage rate. This represents the change in the returns to work.

From 2026 to 2028, the OBBBA would increase the after-tax wage rate by between 3.1 and 3 percent. After the expiration of the Trump campaign proposals, marginal rates would rise slightly but still be lower than under current law. As such, the OBBBA would increase the after-tax wage rate by 2.3 percentage points between 2029 and 2035 and in the long run.

The OBBBA includes dozens of provisions that both reduce and increase marginal tax rates on work. These two effects are partially offsetting, leaving only a modest increase in work incentives.

The most important provision that reduces marginal tax rates is the across-the-board reduction in statutory tax rates, which permanently increases the after-tax returns to work. In addition, the Trump campaign proposals to exempt overtime, tips, and the deduction for seniors would all marginally increase after-tax wages. However, these provisions expire in 2029.

At the same time, a handful of changes, in isolation, increase marginal tax rates. For example, changes to itemized deductions. Under current law, the net marginal tax rate on work is the sum of federal, state, and local taxes, net of the deduction for state and local taxes. The OBBBA, however, caps the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction, reduces the generosity of the home mortgage interest deduction, and increases the standard deduction. As a result, many taxpayers can no longer deduct state and local income taxes at the margin, raising their net state and local income tax rate.

Impact of OBBBA on Investment Incentives

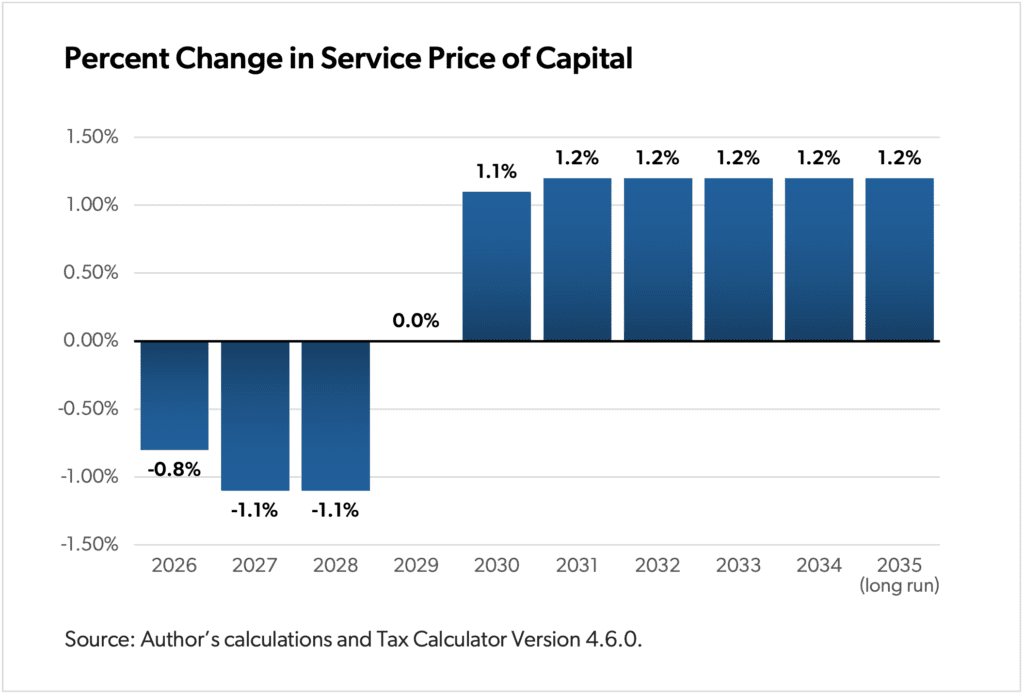

The impact of the OBBBA on the incentive to invest also varies over the budget window. The figure below shows the percent change in the service price of capital for private capital: C corporations, pass-through businesses, and homeowner occupied housing. The service price of capital represents the minimum gross return required for a new investment to break even. The service price represents the cost of new investment and a reduction in the service price increases the incentive to invest.

In the first few years, the bill modestly reduces the service price of capital by between 0.8 percent and 1.1 percent. After the expiration of the temporary business provisions and expensing for manufacturing structures and in the long run, the service price of capital is actually higher than current law, ultimately rising by 1.2 percent.

OBBBA’s impact on investment incentives varies by sector (Table 1). In the first three years, private businesses (C corporations and pass-through businesses) see a significantly lower service price. This is due primarily to 100 percent bonus depreciation, expensing of R&D, loosening of the net interest deduction limitation, and expensing of manufacturing structures. Once the business tax provisions expire after 2029, the service price of capital will be 0.3 percent higher for C corporations due, primarily, to Section 899. In contrast, pass-through businesses permanently see a 2 percent lower service price due primarily to the permanent extension and expansion of Section 199A.

Homeowner-occupied housing, in contrast, would face a tax increase throughout the budget window. OBBBA will tighten the cap on home mortgage interest, cap the state and local tax deduction, and generally reduce the amount of taxpayers will itemize their deductions. As a result, fewer taxpayers will be able to deduct interest on new investment and property taxes, increasing the cost of new homes.

Table 1. The Impact of OBBBA on the Service Price of Capital by Major Sector

Source: Author’s Calculations and Tax Calculator Version 4.6.0.

The OBBBA would also marginally improve the incentive for households to save. This is due to marginally lower statutory tax rates on interest income (due to the statutory tax rate cuts) and a small expansion of tax preferred savings accounts.

Long-run Macroeconomic Implications

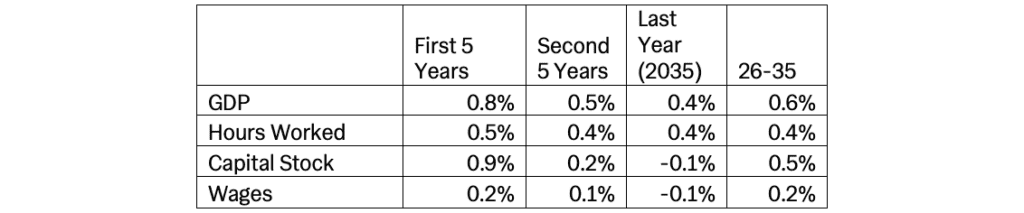

On net, the OBBBA will marginally increase long-run economic output (Table 2). In the long run, the level of gross domestic product (GDP) will be 0.3 percent higher than it would otherwise be. The higher output would be due entirely to a 0.4 increase in hours worked by individuals, which is equivalent to 461,300 full-time equivalent jobs.

Table 2. Long Run Macroeconomic Impact of the OBBBA

Source: Author’s Calculations

As discussed above, the OBBBA would increase the service price of capital in the long run. This would result in a 0.4 percent smaller capital stock. The reduction in the capital stock would result in a reduction in labor productivity in the long run. As a result, pre-tax wages would fall by 0.1 percent.

Note that the long-run analysis isolates the impact of the tax changes and assumes that the federal deficit is held constant. As such, it does not incorporate the impact of federal borrowing on investment, saving, and economic output.

10-Year Macroeconomic Impact and Dynamic Revenue Estimate

The OBBBA will also affect economic output within the budget window. As discussed above, OBBBA’s impact on incentives differs across the budget window, providing a larger incentive to work, save, and invest in the first five years than the second five years. Furthermore, the OBBBA, as written, impacts budget deficits over the next decade—increasing borrowing by $2.4 trillion. Federal borrowing will result in some combination of a reduction in domestic investment or increase in foreign holdings of US assets, ultimately reducing output or national income.

Table 3. Macroeconomic Impact of the OBBBA Between 2026 and 2035

Source: Author’s Calculations

The OBBBA would have its largest impact on output in the first five years of the budget window (Table 3). On average, the level of output (0.8 percent), labor supply (0.5 percent), the capital stock (0.9 percent), and wages (0.2 percent) would be higher than it would otherwise be in the absence of the OBBBA. This is primarily due to the business provisions in the bill that reduce the cost of capital for private businesses significantly.

In the second half of the budget window, the OBBBA’s impact on the economy would begin to wane. Output, for example, would be 0.5 percent higher than otherwise. This is due to three factors. First, Trump’s campaign proposals (tips, overtime, etc.), which increase hours worked by roughly 0.1 percent, expire. Second, the expensing and other business provisions would expire, resulting in a net increase in the cost of capital. Third, additional federal borrowing would begin to raise interest rates, further increasing the cost of capital.

The economic impact continues to fall by the end of the budget window, although the economic impact remains generally positive. Output and hours worked are projected to be 0.4 percent higher than under current law projections by 2035. However, the capital stock would be 0.1 percent smaller due to the higher tax burden on capital and higher interest rates due to increased government borrowing. Wages would be unchanged.

The additional output over the next decade (an average increase of 0.6 percent) would modestly broaden the income and payroll tax base, resulting in offsetting dynamic revenue gains. According to the JCT, the OBBBA would reduce revenue by $3.8 trillion between 2025 and 2034. Accounting for the additional economic growth, from above, would offset $356 billion over the next decade, resulting in a net reduction in federal revenue of $3.4 trillion. After incorporating the spending reductions in the bill, the net cost after economic growth is $2.1 trillion over a decade.

Table 4. Conventional and Dynamic Deficit Impact of the OBBBA

Author’s Calculations, Joint Committee on Taxation, and the Congressional Budget Office

Brief Overview of the Methodology

The model used to produce these estimates is the same used in Pomerleau and Schneider (2024). The model is a comparative statics model of the US economy. The model uses a Cobb-Douglas production function with constant returns to scale. The model includes six sectors: general government, C corporate businesses, pass-through businesses, households, nonprofits, and government enterprises.

Changes to the long run size of labor supply is a function of the after-tax wage rate. The after-tax wage rate is the average pre-tax wage reduced by the weighted average marginal tax rate on wages and salaries. The model uses a labor supply elasticity consistent with the Congressional Budget Office of 0.24—which assumes that labor supply rises by 0.24 percent for each 1 percent increase in the after-tax wage rate.

Changes to the long-run size of the capital stock are a function of the service price of capital. The service price of capital is the minimum pre-tax gross return required to break even in present value on new investment. The service price is equal to the sum of the pre-tax return demanded by shareholders and economic depreciation, grossed up by any entity-level taxes on investment.

In modeling changes to the capital stock, the model assumes that the US economy is a large open economy. This is modeled by blending two modeling approaches: a perfectly open economy and a closed economy. For the open-economy simulation, the after-tax return on investment (before shareholder taxes) is assumed fixed in the long run. For a closed economy simulation, the after-tax return (and thus the service price and the size of the capital stock) are a function of the savings rate. Private saving as a share of national income is a function of the after-tax return on saving. The model assumes that saving as a share of national income rises by 0.2 percent for each 1 percent rise in the after-tax return on saving. For the final simulation, the two pre-tax returns are blended (80% fixed, 20% determined by the savings rate) to determine the firm’s discount rate in the service price.

For the budget window analysis, the model assumes that the capital stock adjusts to its long-run desired level at 5 percent per year (Barro and Furman, 2018). The model also assumes that a 1 percent increase in debt as a share of GDP increases interest rates by 2 basis points.

Marginal tax rates on various sources of income (wages salaries, pass-through business income, interest, dividends, capital gains) were estimated using Tax Calculator version 4.6.0. Other parameters used to calculate the tax burden on saving and investment are consistent with those in Pomerleau (2020).